We are very happy to announce that our project Open Shore is the winning proposal of Shore to Core, the international design competition to reimagine downtown West Palm Beach as a dynamic, resilient waterfront city! We are thrilled with the great reception that the project has had, and eager to continue its development side by side with the people and the institutions of West Palm Beach.

Here we share the press release from Van Alen Institute:

Van Alen Institute and the West Palm Beach Community Redevelopment Agency (WPB CRA) today announced Open Shore by Ecosistema Urbano as the winning proposal for the Shore to Core waterfront design competition. The Shore to Core competition invited international designers, planners and architects to envision what the future of the West Palm Beach waterfront could look like over the next 20 to 30 years, taking factors including populations, economies and the environment into account. The winning proposal will serve as a “vision board” for the city’s future, providing a starting point and framework to help the city adapt and make the most of the waterfront.

Selected from a pool of over 40 international teams and two finalists, Ecosistema Urbano’s winning proposal envisions a healthier and more resilient downtown and waterfront for West Palm Beach—a keystone city in southern Florida with a growing population of people in their 20s and 30s, as well as large Black and Hispanic populations. The competition proposals imagine new amenities that reflect the city’s emerging populations, and Shore to Core’s organizers believe that design is a crucial tool for tackling these evolving needs. The initiative included public consultation, and this input played a role in the jury’s decision-making process.

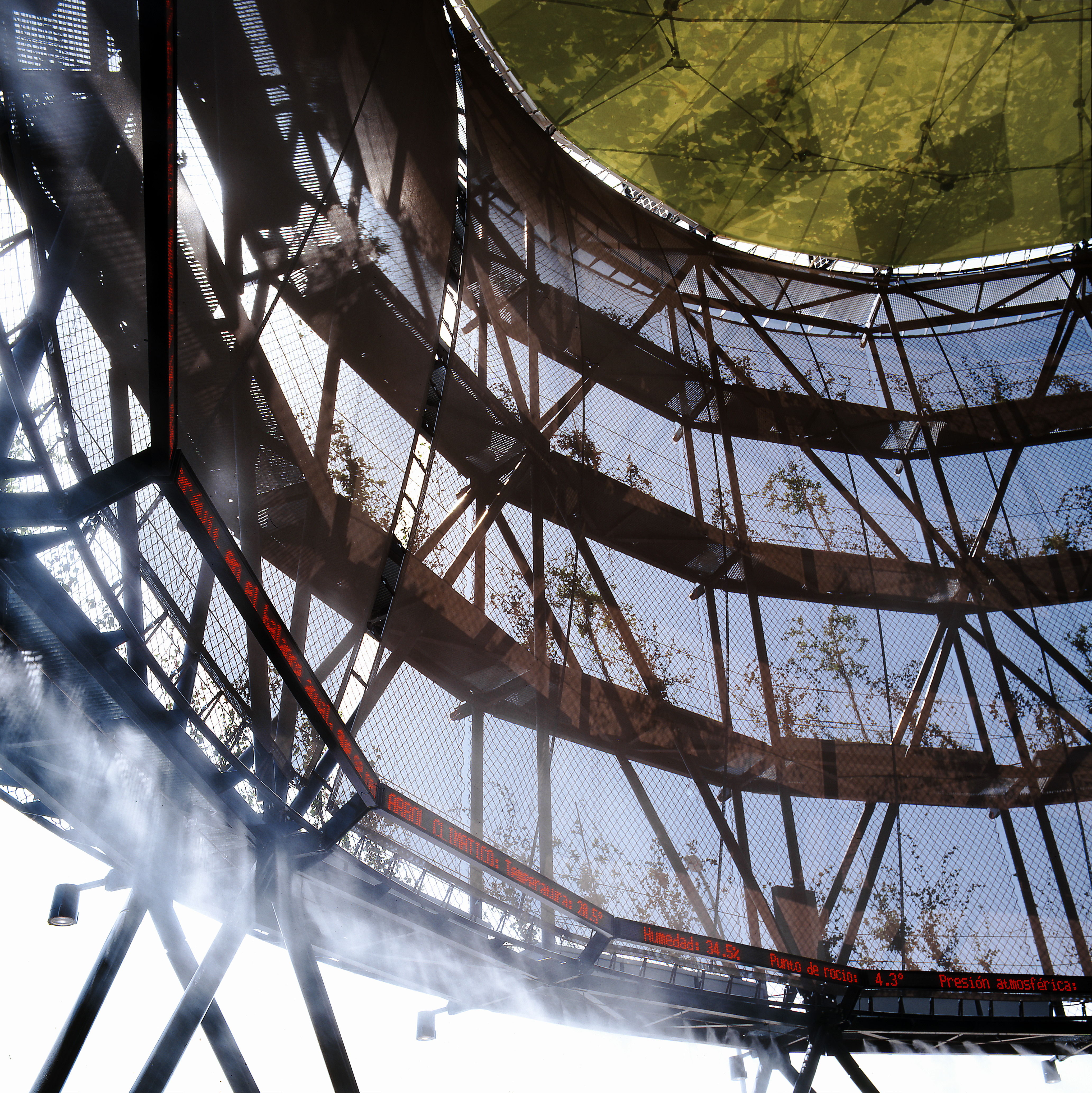

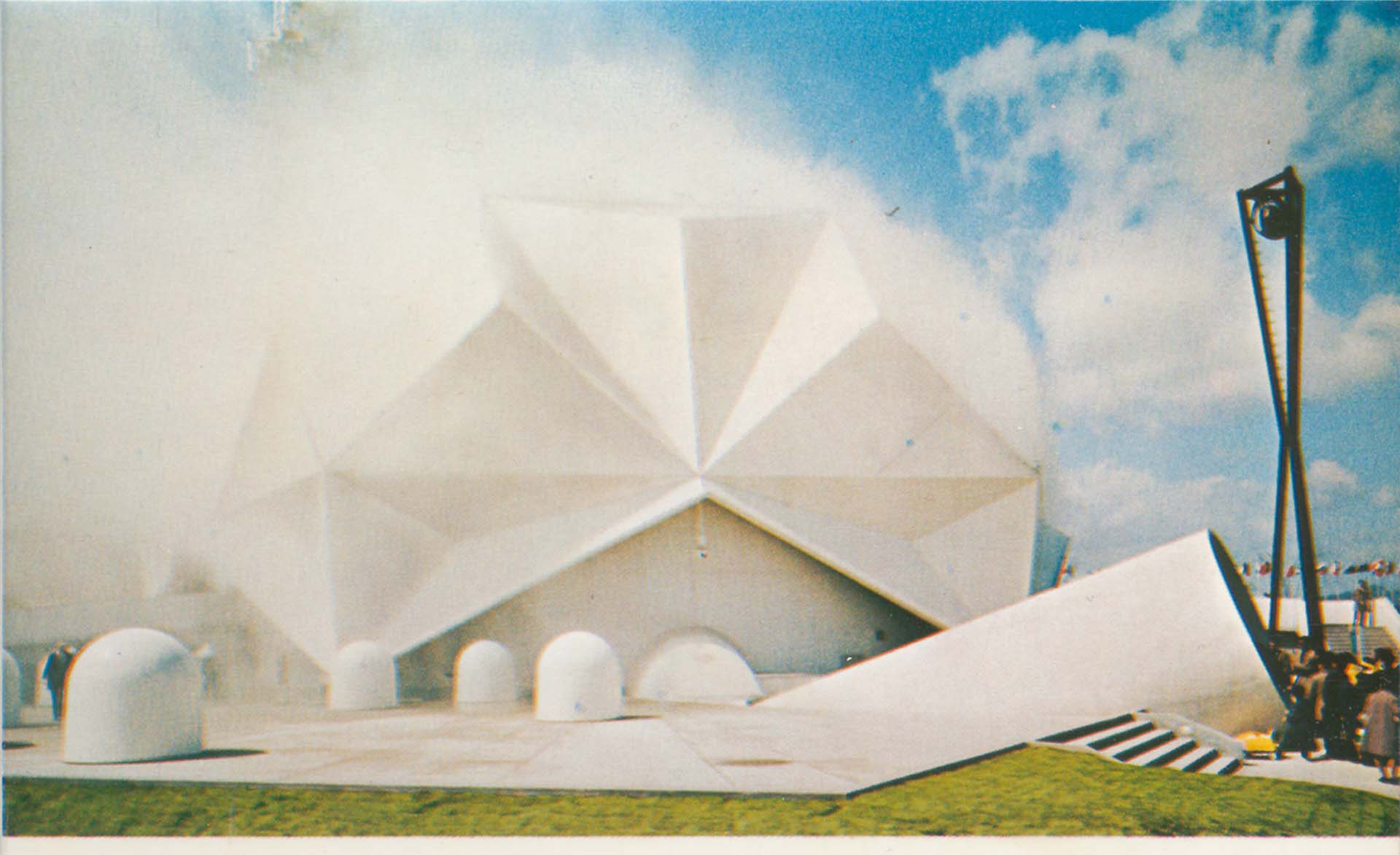

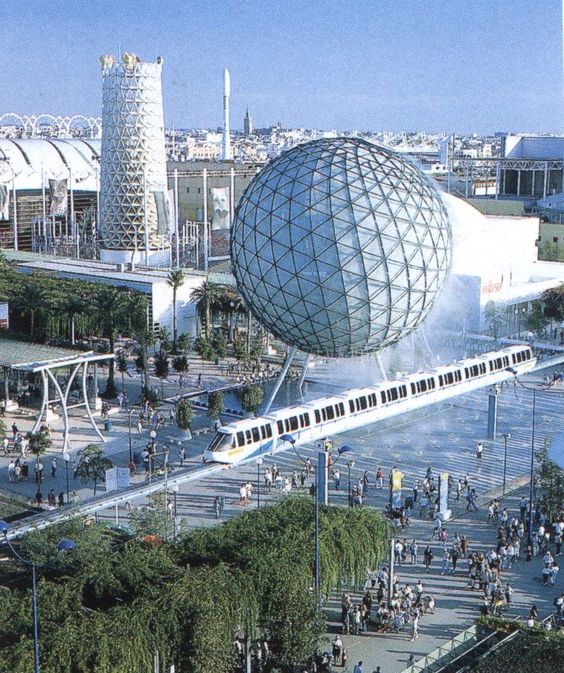

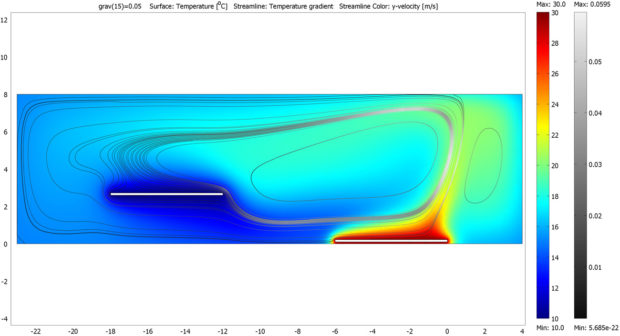

Ecosistema Urbano’s winning design answers Shore to Core’s call for a comprehensive, forward-thinking urban plan to make West Palm Beach’s waterfront a year-round destination for locals and visitors alike. The proposal includes what could be the first public bioclimatic domes in the U.S. adorned with hanging gardens. These domes create climatically comfortable spaces 365 days a year, thereby supporting a more socially cohesive city.

The proposal also illustrates how the city’s Banyan Garage could be upcycled into a mixed-use building with both public- and private-sector roles featuring adaptive climates suitable for a range of activities, including a farmers market, coworking spaces, and skyline viewing platforms. Additional amenities include vibrant thematic alleyways—with such features as a rock climbing wall, interactive exhibition space, and immersive foliage—that harness the cultural values and experiences unique to West Palm Beach, while also providing shade and introducing new elevated programming spaces

Ecosistema Urbano | Open Shore | Banyan Hub | Section

Ecosistema Urbano will present their proposal to the WPB CRA board in May 2017. The CRA board will identify priority projects within the Banyan Garage and downtown alleyways, and then contract with Ecosistema Urbano. This process will be followed by outreach to the community about the individual elements that are scheduled for possible implementation in late 2017 or early 2018.

“The Shore to Core competition and resulting proposals truly offered insights into how we can plan a strong and vibrant future for our city,” said Jeri Muoio, Mayor of the City of West Palm Beach. “Ecosistema Urbano’s design was applauded by all as enhancing the waterfront and creating new, iconic experiences that incorporate our natural resources, cultural spaces, and inclusive urban atmospheres.”

“Ecosistema Urbano’s proposal addresses social cohesion in a compelling way by integrating locally responsive systems with a welcoming public space that will further diversify the city,” said David van der Leer, Executive Director of Van Alen Institute. “We’re thrilled that West Palm Beach is looking to the future and rethinking how to create a downtown that is uniquely theirs— a downtown that enhances the wellbeing of residents and visitors alike.

The runner-up design finalist, Perkins + Will, created a proposal focusing on community-building with a continuous waterfront park, extended Great Lawn, and the Banyan Garage revitalized as a multi-use civic space. Van Alen has synthesized the work of the finalist teams into a key findings document, “A Shore Thing: Key Findings from the Shore to Core Competition,” that summarizes the shared insights from all three proposals.

The Shore to Core competition has parallel research and design tracks: The aim of this structure is to understand how waterfront cities like West Palm Beach can become healthier, and to create design strategies that will make them more responsive to rising sea levels. The winning research team, Happier by Design, focused on how specific types of public spaces may increase the wellbeing of people who use them, and conducted a pilot study analyzing the health benefits of more complex and engaging urban landscapes.

By testing environmental psychology principals with tactical urban interventions, Happier by Design found that public space designs that boost feelings of fascination foster wellbeing. The research team also recommended that designers focus individuals’ attention on nature and create spaces that are both comfortable and interactive, including such features as movable seating and adjustable lookouts that frame the landscape. The team’s recommendations affirm the dynamic and engaging designs proposed by Ecosistema Urbano. The combination of innovative research and original design in Shore to Core reflects Van Alen’s mission to use research and design to inform the planning of new civic spaces.

To read the final reports, see:

Key Findings | Van Alen Institute

Open Shore | Ecosistema Urbano (Design Winner)

Happier by Design | Happy City, University of Virginia, StreetPlans and Space Syntax (Research Winner)

Adapt to Thrive | Perkins + Will (Design Finalist)

Competition Jury:

Raphael Clemente, Executive Director, Downtown West Palm Beach

Colin Ellard, Associate Professor, University of Waterloo, Department of Psychology

Patrick Franklin, President and CEO, Urban League of Palm Beach County

David van der Leer (Jury Chair), Executive Director, Van Alen Institute

Jeri Muoio, Mayor, City of West Palm Beach

Penni Redford, Sustainability Manager, City of West Palm Beach

Manuel Clavel Rojo, Clavel Arquitectos (substitute for Terry Riley, K/R Architects)

Jon Ward, Executive Director, West Palm Beach Community Redevelopment Agency

Lilly Weinberg, Director of Community Foundations, Knight Foundation

Claire Weisz, Founding Principal, WXY Studio

Nancy Wells, Professor, Cornell University, College of Human Ecology, Design and Environmental Analysis Department

Ecosistema Urbano Team:

A multidisciplinary Madrid and Boston-based team comprised of principals Belinda Tato and Jose Luis Vallejo; Marco Rizzetto, Carlos León, Antonella Marlene Milano, Luisa Zancada, Jorge Toledo, Marta Muñoz, Pablo Santacana, Lola Pouchin, Maria Vittoria Tesei, Andrea Bertrán, Ana Patricia Maté, Lucía De Retes Cascales, Cristina Rodríguez, Elizabeth Kelleher, Lorena Tselemegkou, Luana Scarpel, Silvia Sangriso, Daniela Menendez, Julia Casado, Constantino Hurtado, Andrés Walliser.

To view high-resolution images for this project, including work by the winning team, click here

To view animated images of Ecosistema Urbano’s proposal, have a look here